It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that when you talk with me for more than five minutes that I am a massive David Lynch fan. His work has had a tremendous influence on my life; I would not be where I am without it. Lynch’s entire filmography is incredible, though The Elephant Man holds a special place in my heart.

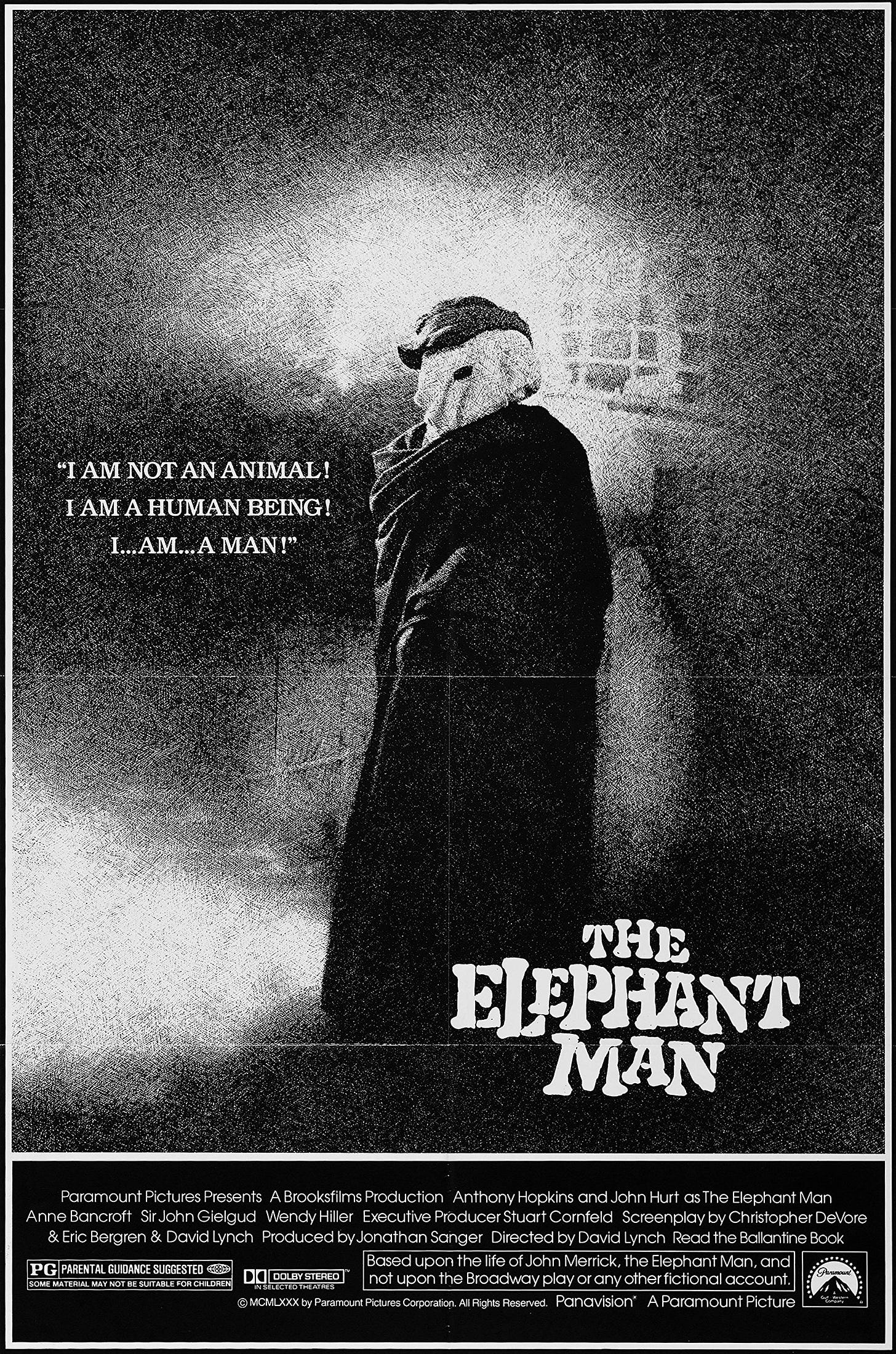

Released in 1980, the film is based loosely on the life of Joseph (referred to as John in the film) Merrick, the titular “elephant man.” In Victorian-era London, Doctor Frederick Treves visits a “freak show,” overseen by the abusive Mr. Bytes, who displays John in front of leering audiences. Taken aback by his physical deformities, Trves convinces Bytes to let him take John to the London Hospita,l where he conducts further examination. After he is returned to Bytes, the latter beats him, which forces him back to Treves’ care to heal. Bytes develops a friendship with Merrick and wants him to stay at the hospital, so he works to prove his intelligence by practicing his speech, which impresses Governor Carr Gomm enough to give him the approval to do so. Merrick eventually branches out, focuses on his art by building a model cathedral, and connects with prominent figures like local actress Madge Kendall, but is still treated by society at large with disgust. Jim, a worker at the hospital, sells tickets and encourages people to come and gawk at Merrick. Bytes kidnaps Merrick and shows him off at a circus, where his physical condition deteriorates further, culminating in Bytes locking him in a cage with animals. His fellow performers break him out and help him travel to England, where an angry mob accosts him, and he exclaims in the most infamous scene of the film: “I am not an animal! I am a human being! I am a man!” Treves rescues him and tries his best to make Merrick‘s final days full of joy, taking him to the theater to see a performance by Kendall. At the night's end, Treves bids Merrick farewell, and Merrick completes his cathedral and lies down on his back, dying.

While I have seen The Elephant Man multiple times, watching it in a theater (and an independent one at that) was a completely transformative experience, as if I were seeing it for the first time all over again. I love revisiting films because with experience comes a new perspective: the way I would watch The Elephant Man in my early 20s is drastically different than how I interpret it now as a woman approaching my mid-30s (still can’t believe it sometimes). Yes, I’m the same person, but I’ve gained new knowledge and grown in the interim as well, so the film gains another layer of resonance because of that.

My whole life I’ve never fit and felt “othered” because of my autism and various mental health diagnoses (PTSD, ADHD, OCD, depression, and anxiety), and it led to me for a long time, having a sense of deep, internalized self-hatred; like I am somehow “defective” or “abnormal,” so on that level, I can relate to Merrick’s struggles. During my elementary school years, I underwent intensive physical therapy and worked with a speech pathologist (I was nonverbal until 4 years old) to work on my balance, coordination, and language skills, and also had an IEP (individualized education program). Without these resources, I would not be where I am today.

It wasn’t, however, until my 30s, if I’m being perfectly honest, that I realized I AM intelligent and that I DO have worth and a perspective that matters. I NEVER thought in a million years that being a college professor would become a reality. Many of us are taught to think that neurodivergent folks like me or people like Merrick are somehow “less than” because of what we have to grapple with on a daily basis, and we are deemed “abject” beings.

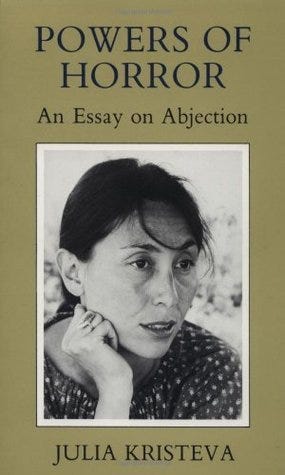

I first learned about the concept of abjection as an undergraduate in the English program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where I currently teach and do campus outreach. One of my academic mentors taught a literary theory course centered around the “meaning of pain” and had an excerpt of Julia Kristeva’s 1980 book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection assigned to us students. Her writing is notoriously dense, but if one were to derive a simple definition of “abject;” it refers to when the connection between symbolic order and subjectivity is severed; what is cast off and set aside is rendered abject. Kristeva further explains, “It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order.” The fact that Merrick’s mere existence subverted normative views of bodily identity lends itself to onlookers viewing him as abject. Despite the fact that the real-life figure of Merrick as well as his film counterpart were able to make great strides and adapt to their surroundings socially at least, Kristeva notes “abjection can constitute for someone...turning away from perverse dodges, presents himself with his own body and ego as the most precious non-objects; they are no longer seen in their own right but forfeited; abject.” By virtue of his physical impairments and the stigmas placed upon him along with being treated as an object of voyeurism, Merrick’s ownership of his selfhood is, to a degree, lost. This is most apparent in the scenes where Jim invites townspeople to the hospital office hours to come into Merrick’s quarters to ogle and demean him. Kristeva also mentions, “if it be true that the abject simultaneously beseeches and pulverizes the subject, one can understand that it is experienced at the peak of its strength when that subject, weary of fruitless attempts to identity with something on the outside, finds the impossible within; when it finds that the impossible constitutes its very being that is none other than abject.” I find this dualistic notion of abjection as described here compelling when applied to the narrative of the film as Merrick achieves fulfillment through art and forging social connections with others, something that he never thought was possible for himself. A question arises, however: can he ever truly escape or transcend his abject identity?

I like to think he does. Viewers and fellow fans of Lynch tend to characterize his work as “surreal,” and while those elements are present (especially in the opening and closing shots, respectively), what is most profound about The Elephant Man, in my eyes, is the way Lynch treats the subject with compassion and HUMANIZES Merrick. He does a fantastic job of exploring the inherent prejudice that Merrich was forced to face his entire life, while contrasting that against the kindness that Treves and a select few extend toward him.

One of the film's most moving scenes occurs when Treves invites Merrick into his home to meet his wife and enjoy tea together. Mrs. Treves is cautious, but approaches Merrick with warmth. Merrick shows her a photograph of his mother, and remarks, “I must have been a great disappointment to her” due to his physical appearance, with Mrs. Treves comforting him and saying t“No son as loving as you could ever be a disappointment.” Merrick ponders: “If only I could find her, so she could see me with such lovely friends here now; perhaps she could love me as I am. I've tried so hard to be good,” with Mrs. Treves shedding a flood of tears. There is a yearning and perhaps pressure on his part to assimilate with “regular” society; he attempts to be deemed worthy, but that shame he carries with him obscures his self-identity, which hits incredibly close to home.

Merrick states “we are frightened by what we don’t understand,” and I can’t help but agree with his observation, as disheartening and true as it is. Anything or anyone that is deemed “different” is automatically seen as a threat to our comfortable and “normal”(whatever that means) existence, but instead of falling into that line of thinking, as Lynch suggests, we SHOULD and NEED to act without judgment and instead, use empathy and care as our driving forces.

If anyone who checked out this piece wants to read more about abjection, I highly suggest these texts:

Abjection Incorporated: Mediating the Politics of Pleasure and Violence (2020), edited by Maggie Hennefeld and Nicholas Sammond

Extravagant Abjection: Blackness, Power, and Sexuality in the African American Literary Imagination (2010), by Darieck Scott

Abject Visions: Powers of Horror in Art and Visual Culture

I like this movie as well. Ive always felt a connection, but I also was inspired by the people who treated him as a person. They are the kind of person to aspire to.

After having the pleasure of meeting you in person for more than 5 minutes, your love of Lynch truly resonates! This is great work. Especially love the message about acting without judgment and prioritizing empathy.